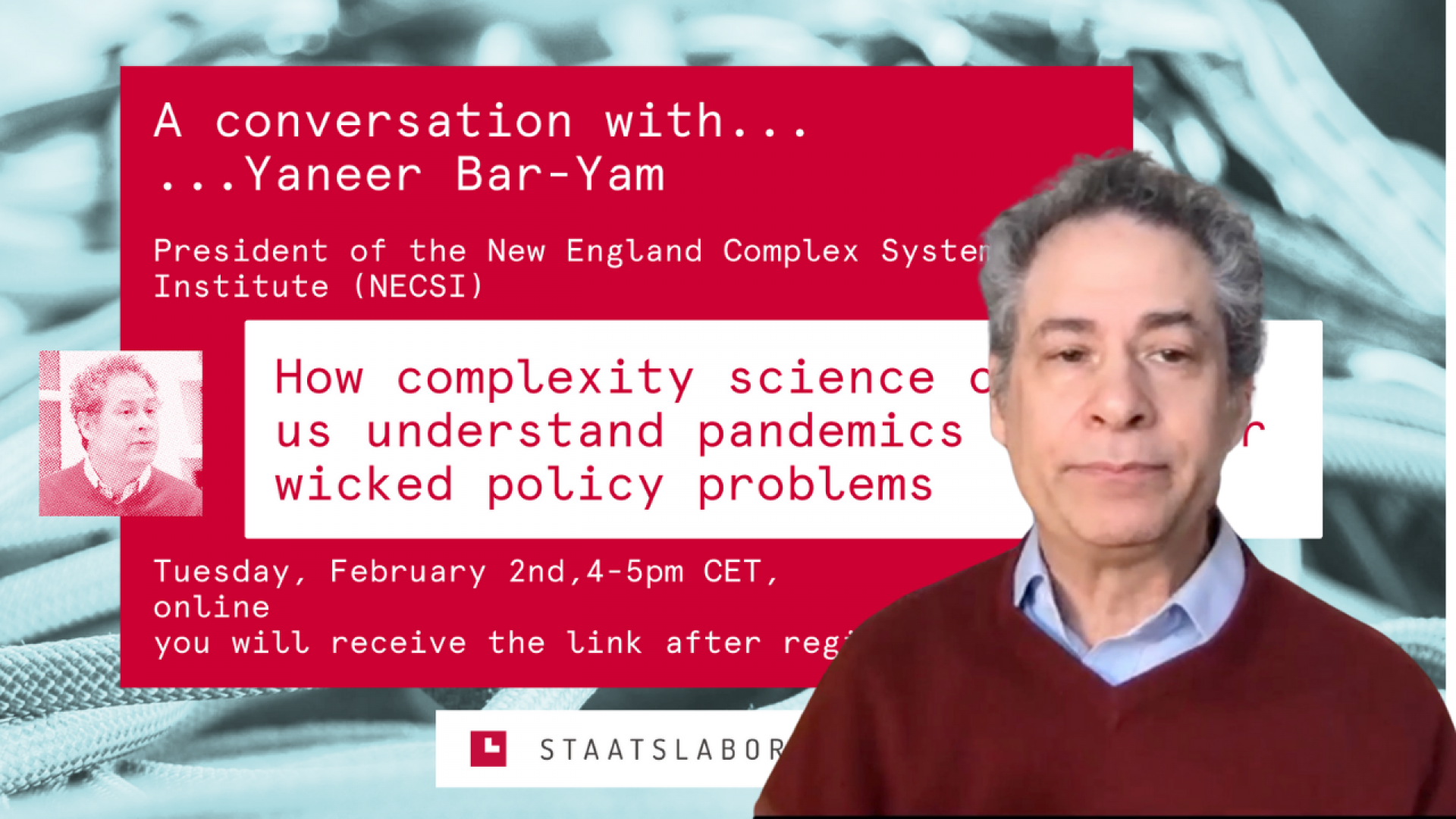

On Tuesday, February 5th, staatslabor held a conversation with Yaneer Bar-Yam on how complexity science can help governments understand pandemics and other wicked policy problems.

Yaneer Bar-Yam is the founding president of the New England Complex Systems Institute (NECSI) and has been a longstanding and prominent advocate for a complexity-informed understanding of policymaking.

An expert in the quantitative analysis of pandemics, he previously advised policy makers on the Ebola epidemic. His prescient analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic, as early as in late January of last year, has drawn much attention to the critical insights that complexity science can deliver to policymakers.

Below you will find a recording of the conversation as well as an unedited and timestamped transcript.

Danny Buerkli (00:04):

Welcome to this conversation with Yaneer Bar-Yam, hosted by staatslabor. We're a not-for-profit government reform and innovation lab working with all levels of government here in Switzerland. My name's Danny Buerkli, I'm a co-founder and co-director of staatslabor. And I'll be your host today, together with my colleague Alenka Bonnard, who's right next to me, also co-founder and co-director.

Alenka Bonnard (00:27):

Good evening. Hello.

Danny Buerkli (00:30):

The purpose of this session here today is, we hope, to enrich [inaudible 00:00:36] debate in Switzerland, with new and potential unconventional ideas. And Yaneer, we're really delighted and grateful that you've agreed to spend this hour with us and speak to the question of how complexity science can help us, can help governments understand pandemics and other wicked policy problems.

Yaneer, you're a physicist and a complex systems scientist. You're also the founding president of the New England Complex Systems Institute, which is an independent research institution based on the east coast in the US. You've also been an advisor to numerous government entities, including the Pentagon, the National Security Council, the CDC, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and many more.

And maybe most importantly for our conversation here, or two things. First, you've worked on the Ebola outbreak quite intensely, and you've worked on pandemics before. And you've also first warned publicly of the dangers of COVID-19 on January 26, 2020, which now feels like an eternity ago, and which was well before most of us, and well before most governments, frankly, had fully realized what was coming our way.

And since then, you've been one of the most consistently prescient observers and commentators and almost anything that you say now has become accepted as common sense. And almost all of these things were controversial at the time. I'm thinking of things like mask-wearing, travel bans, the role of aerosols, and so on and so forth. You, for the most part, got there first.

So we kind of got to ask, how is it that Yaneer has been so consistently right in this pandemic? How is it that you've been so consistently on the money, so to speak? I'd be keen to hear what your answer is, but the answer lies, I believe, in large part in your background in complex systems science, which is a rather uniquely powerful way of thinking about pandemics and other complex public policy problems.

So we'll hear an introduction from you, Yaneer, for about 15, 20 minutes. Alenka and I then have a couple of questions prepared. And then we'll open it up for questions from the floor. Now, with all of that out of the way, we're delighted that you all are here. A warm welcome again. Thank you for so much, Yaneer, for being here. And the floor is yours.

Yaneer Bar-Yam (03:18):

Thank you. And thank you for inviting me. I want to start by imagining that you go out to your car... And nowadays that may take some time if there are restrictions on travel. But let's say you go out to your car and somehow you have amnesia. And your brain is fine, but you don't remember what driving is about. The question is: what would you do in order to figure out what to do? And the answer is: it's kind of hard, right? Maybe you would look around and you would see things, you might try to pull on the hood or pull on the doors. Maybe you'd get a door open. But you probably might end up in the backseat just like you might end up in the front seat.

The purpose of complexity science, as I understand it, is to figure out what are the control variables in a problem. So if you knew that the steering wheel and the brakes and the gas and the gearshift were the things that you need to control in order to control the car, you would know how to drive a car. Roughly. You would have to maybe experiment a little bit. You would have to think about it. Maybe do some modeling. But basically you could figure it out. But if you didn't know that those were the things you had to control, it would be very hard to figure out what it meant to drive a car.

And so complex systems is the science that takes us beyond the mathematics of calculus and statistics. And so the point of the fundamentals of the sciences that physicists figured out, that calculus and statistics didn't describe the real world because they got the wrong answers. When they talked about a system and they did a calculation, they just got the wrong answer and so they had to invent the new math. And if you want to look at some of this history, there was a paper called Why Complexity Is Different that you can read that I wrote a number of years ago, it introduces these ideas.

But the basic challenge in dealing with complex systems is that there are all of these variables that the system depends on. And if you don't know which one or ones to think about, there then are two choices. Either you pick one, like the average height or the average wealth or something like that, and you use that as your variables. Or, you try to map out all of the variables in a system. And there are parametrized problems with 50,000 or 100,000 variables, and therein lies madness, of course, because you can never write down all the variables.

So the trick, or the fundamental methodology, that I use in complexity science is a methodology called renormalization group, that dates back to 1970 in studying phase transitions like boiling water, which enables you to figure out which variables are actually the important variables. They are then the control variables in a problem. Okay?

Yaneer Bar-Yam (06:52):

I'm happy to take questions. And it might be good if someone has a quick question that this was not understood, you can ask. But I'm going to move in directly to pandemics in a moment, so if you have a question about this, either write it down so I can answer it later, or you can chime in.

In any case, I have been studying many different problems using this method. And the reason is that, well, if statistics doesn't describe the world because it doesn't describe dependencies that exist in the world, then there are a lot of problems that you can make progress on by thinking about the mathematics that will help us understand those problems.

And one of those problems started when I was studying the evolution of pathogens and their interactions with hosts. And what we did is we studied how long-range transportation, like adding flights from Zurich to Bogota or something, or to Tokyo, to think about what the effect of such long-range transportation is on the dynamics of pathogens. And there is an obvious statement that you can make, which is that pathogens will travel faster. But it turns out that there's something fundamentally different that you can say, which is that there is a phase transition from a condition of local outbreaks and extinctions to global extinction at a fairly small amount of transportation.

Now, this is a paper... I wrote this in a paper in 2006, and in that paper we warned specifically about Ebola and SARS-like diseases. And the reason, of course, is that if these diseases escaped local conditions, they would become global threats. And it's scary because we think about things as changing gradually, right? If we add long-range transportation, then it's going to go a little bit faster. A little bit more long-range transportation, it's going to go a little bit faster. But what the theory says is no. You can be in a stable circumstance and add a little bit of long-range transportation and all of a sudden you're in an unstable regime to global extinction. That's scary.

Now, I made a presentation on this many... Because I was trying to get people to take this seriously, and honestly, it wasn't easy, but I made a presentation on this in Geneva in January 2014 at the headquarters of the World Health Organization. And when I made the presentation, it was about a five-minute presentation, people's jaws dropped. You could see it. And of course, the reason is that people think about the future in terms of the past. That's what statistics is, right? The past information tells you what the future's going to be because you know what happened, you know what's going to happen. Right? Makes sense? Well, sometimes it makes sense. But what I was saying is that that wasn't true.

Yaneer Bar-Yam (10:29):

Well, they took my research seriously but they didn't do anything new really. And March of that year, Ebola broke out in West Africa and became out of control by spring/summer. And I got involved. I was advising because of other work that I'd done on global hunger and ethnic violence, and we might talk about that some time. But I was advising the National Security Council, the CDC, the UN, the head of the UN response on the outbreak. And the basic explanation that I gave, which comes from the math, is that if you cannot control it at an individual level, you have to go up to the community level. You have to treat communities as being infected in order to stop the outbreak. You can imagine, as you might, that governments are not always rapid to respond.

And so it turns out that I was put in touch by a friend with a small NGO in Liberia, they put me in touch with the people who were working on the outbreak response. Second week in October, I spoke with them and I said, "How are you doing?" and so on. And I said, "Well, what about trying this?" and they said, "Oh, yeah. We started doing that three weeks ago." So what happened was members of the community went door to door in teams identifying early fever. Instead of waiting for people to show up in the hospital bleeding and doing contact tracing, going back into the community and trying to figure out who they were in touch with, people went in the neighborhood around, found out who had early fever, isolated them. The outbreak went up exponentially, went down exponentially, went extinct.

Now I have to tell you that my colleagues that I was talking with who were the people who had been studying outbreaks for a while, what they told me was that it was going to go to burnout. That term was for what we call now herd immunity. But it meant basically 50% or 10 million people would have died in West Africa. And that's if it would have stayed there. It turns out that we stopped it at 11,310 deaths in the three countries that it affected in West Africa. Maybe a couple in other places. And the reason that it happened is because people changed behavior. And that was the thing that everyone was telling me was impossible. And that's been one of the things that we've been hearing during this outbreak.

So I worked in West... Worked in? I worked on the effort in West Africa. They did it. I didn't. I just basically explained to everybody else what they did. And then I worked on outbreaks in the Congo, leading up to starting working on this on January 26, as Danny mentioned.

So where are? Let's talk about the relevant variables, the things that control outbreaks. There are two things that people don't think about that are super important, right? These are the steering wheel and the gearshift. The brakes and the gas, we know that's R. R is greater than one, it goes up exponentially. R is less than one... That's the control variable everyone knows. But the other control variable that we need to know is travel. Limiting travel is an essential variable. If you don't have travel, you don't have a pandemic. If you do have travel, you control of travel is a control parameter. It enables you to regulate the intercommunity transmission. And if you can control intercommunity transmission, you have a tremendous ability to control an outbreak.

Yaneer Bar-Yam (14:39):

The second thing, and I want to show you... Maybe I'll show you a picture of this. The second this is zero. The way to say it mathematically is the discreteness of the number of cases. If you're at zero it's a very different number because R doesn't matter. Right? Because if you have zero then no matter what R is it's still zero. But if you have anything other than zero, it will always follow R, ie. increase exponentially if it's greater than one.

And that's the most important two things that we need to know. And if you know that, then what you end up with is a very clear strategy. And there is only this strategy. We call it the Green Zone Strategy. The Green Zone Strategy says: you limit travel as much as possible, you suppress the outbreak locally, and you open up zones at zero. That way you can rapidly open up zones and rapidly expand, and we have experienced with this disease that it works.

In fact, the only real condition to use this is that you can get exponential decline. As soon as you can get exponential decline by controlling R, you can get to zero locally, you can expand local regions, and expand them progressively. So you can start with a household and a neighborhood. You can do a city block. You can do a neighborhood. You can do a city. You can do a county. You can do a country. You can do a continent. As long as you keep the ratchet going so that you're only going in the direction of improving the situation.

And we have papers about this I can give you to read, but let me show you a couple of pictures. Because we know this has worked, and worked well, in multiple countries, including originally in China but, of course, in Australia, New Zealand, in Singapore, in Thailand, in Taiwan. It's all about regulating travel, whether it's within the country or between countries.

And let me just say in advance of talking about Switzerland, that Switzerland is ideal for this. You couldn't have a country that's better suited that's a land-based country, because the geography and the culture and the society is all oriented around mountain divisions, lakes, and cantons. And there's all of this history about the differences. I mean, I've studied this in Switzerland quite a bit because of other work on the subdivisions and the natural behavior of Switzerland.

Yaneer Bar-Yam (17:22):

Let me just show you a couple of pictures for right now. So can you see this? Yep. So this is China's outbreak. And remember they had no information when they started, but they still did an incredible job. Here are county provinces in this case, right? Provinces across the right. And I can make this bigger, but you get the picture, right? And this was the epicenter in Wuhan, this is Hubei province. And the colors are showing number ranges which you can figure out visually. If you want to look at details, I can show you this. This is a long time picture, it goes from January to the middle of March.

So what we see is that there was the outbreak here. It went up to a few thousand, like three thousand in the center, and then their other provinces, and it expanded outward. Then there's the lockdown that happened here. The continued dynamics up is the fact that you don't see all the cases, right? The cases are not known because people have been infected. But then once you've stopped it, then you end up with it going up and going down, and then going away. And here it's at zero in almost all of China, with the exception of this. So this is a five-week period, and this is the classic amount of time it takes. It takes five to seven weeks.

And the reason it takes five to seven weeks is because of the incubation period. Basically, it takes two and a half incubation periods in order to stop an outbreak, if you do it well. And if there's a lot of cases, it takes a little bit longer. There's a logarithm, a weak dependence on number of cases, but it's not that strong. And after seven weeks, and even before, even in Wuhan, things are safe.

And the reason that they're safe is that almost all the cases after six weeks are already isolated, right? They're in quarantine because you've identified cases, you've taken close contacts, you've put them into quarantine, so the new cases that show up are actually people that are already quarantined.

We can now look at other countries. Here I can go down here. This is Switzerland. And in Switzerland you see, again... This is what people call the first wave, but it's really the first allowing the disease to come in. The disease didn't have to come in altogether if we'd done travel restrictions at the beginning. That's why I wrote my paper in January to try to get everyone to do that. But given that people didn't, right, it grew.

Yaneer Bar-Yam (20:07):

That there was a lockdown. The lockdown was successful. There's this geographic contraction. There's this residual cases which could be, for a number of reasons, either travel or not quarantining away from home, or other kinds of things. So that is something that's a detail that should be understood. And then of course, the restrictions were relaxed, people were then allowed to go back. Again, it's not zero. If it's not zero, it will grow. If you don't have travel restrictions protecting green zones, then it grows back. And that's what we've seen all over the world.

I just want to show you... So this is Italy. Italy, of course, had this outbreak. They had a really, really slow decline. And the reasons that R was so close to 1, it was like 0.98 and they had four months of decline before they opened up. That's a huge amount of time. Probably has to do with insufficient travel restrictions and insufficient quarantine away from home, right? Because if you allow people to infect each other at home, it really causes a lot of problems.

But I want to show you this. This is Russia. Russia is the longest country in the world. Look at this. The whole Siberian railroad length gets infected because they never effectively applied travel restrictions. Absolutely astounding. And totally, totally different from what happened in China, right? So you could call this fail. All right?

So now let's go back and talk about sort of the basic strategy and where we are. I few more comments that may be helpful. So recently we had a presentation, I really recommend you listen to it, anybody who can find that. Oh the graphs, I think they're on our website. If you ask me, I will tell you. We have a couple of websites. There's necsi.edu is my home website. That's NECSI. A month after my original paper at the end of February, we started the organization endcoronavirus.org, which is a volunteer organization to stop the outbreak, and now we have other... I'm participating in other groups.

Recently, there's particularly a lot of action in Germany. There's a group of scientists in Germany that have put out a strategy that's gotten in all the newspapers. If you haven't read it, just look at almost any newspaper, I guess, in the last week, the last couple of weeks, or week and a half or something. And there is interaction with the government there, and hopefully the Green Zone Strategy will be adopted. There's also been progress in Ireland, in terms of adoption and a lot of discussion there, hopefully that will happen too.

Yaneer Bar-Yam (23:06):

And of course, more generally in other countries there's movement, particularly in view of the new variants, right? The new variants basically make it so unreasonable not to control the outbreak. I mean, the first one, as far as I'm concerned, was unreasonable, but, of course, now it's a lot worse. And not only that, of course, the variants are getting worse and will get worse. It's the very counter, by the way...The fact that they get worse is counter to thinking in the regime where you have local outbreaks, the outbreaks are self-regulating so that pathogens get less bad. And that's what people learn in school.

But if you have long-range transportation, it goes the other way. You end up with having the worst possible diseases rather than the quote best possible diseases. So that's what we're experiencing. So the variants are getting more transmissible, they're getting more lethal, they're also evading the vaccine. At least, beginning to. And, surely. if there is one that is already evading the vaccine a little bit, then there are many others that are evading it even more.

So the whole idea of the vaccine as a silver bullet doesn't make any sense in the context of a widespread disease. It makes sense as a tool that can be used, particularly when the disease is low, but surely not as a way of getting to zero in a widespread disease. I mean, maybe there's a chance of one in I don't know how many that it would work that way, but that's just not the way it generally works.

So what I wanted to do is to talk about... The elimination strategy was adopted in Australia, which is a huge country with multiple states, in New Zealand, and so on. And it's really kind of interesting to hear how they talk about it. We have some presentations by Ian Town, the chief scientist of the Ministry of Health in New Zealand, and also Michael Baker, who was the architect of their response. But basically, they knew that elimination was a possibility, and once you know that it's a possibility, then it's kind of obvious that it's going to be better.

And all of the idea that you can balance economy versus disease doesn't make any sense, right? Because if you have to live with a disease, then you have to think about balancing something against something. But if you can get rid of it, then you go back to normal. So if you can do it over a short period of time, five to seven weeks, there's just nothing else that makes sense.

Yaneer Bar-Yam (25:56):

And especially in Switzerland where you have natural geography, and a community that is able to execute, and we've seen that they can do it. And if one says, "Hey, we're going to do this. Let's get it done," it's going to happen and you're going to be back at normal, a pre-COVID normal, with some international restrictions until Germany and France and Italy and so on decide that they've got to do it too. Which, of course, if Switzerland was successful in doing it, everyone would say, "Oh. Oh, yeah. I guess that's the right thing to do."

So in any case, let's talk about a couple of pieces that came out recently. There's an editorial by the chief editor of the Lancet, on I think it was just this past Sunday, if you haven't seen it, that basically says that no COVID strategy that the German group has put together... And there's a really great last line in that article that really should be read. Can someone find it? Danny, can you find it and read that last sentence?

And there's a Guardian piece that was written by a UK epidemiologist and Michael Baker that is basically the 16 reasons to go to elimination. It's really outstanding piece. If you haven't seen it, it's in the Guardian. And again, someone should find the link and put it into the chat.

And just to go back to this, Switzerland is super ideal for doing this. There's natural ways of doing it geographically. And I get it that everyone's worried about sort of limiting travel and so on, so on. After all, it's only been in the last generation that we have this really comfortable European travel and it gives so much benefit and everyone likes it, so as they can go shopping in who knows where, and everything that they want to do. But the bottom line is this is temporary.

And if you think about it, if everyone assumed that everyone else was rational, everyone would go to zero because they would assume that everyone else would go to zero, because there's no other rational choice in terms of people's own action. And so from a traditional economics perspective, what everyone has been doing is assuming that everyone else is super irrational. Which is kind of interesting sociologically. But the bottom line is, let's just get to zero and if there's European cooperation, there's really no reason not to make sure that this happens.

Yaneer Bar-Yam (28:36):

But again, there's no reason to wait, right? Getting to zero is only beneficial for oneself. You can open up normally, you can go to restaurants, and have schools open safely. And I can tell you, I know that schools are open in Switzerland. If you want to ask me about it, we just have an article about long COVID in kids. Over 50% of kids have long-term symptoms, even if they have asymptomatic or low symptomatic cases. It's called paucisymptomatic now. And almost 50% in this study have symptoms that are affecting daily life of kids. And this is just not acceptable. It just really shouldn't be happening. So schools, for many, many reasons, including transmission, including disease, should not be open. And if you want to challenge me on that, I'll go through the literature about this.

But there's an idea... Look, there's a lot of people in the West who are sort of down on China. But there's actually an interesting puzzle. I don't know if you've seen this, these Chinese finger puzzles? Where you get your fingers into something and you can't pull out? Have you ever seen this? But the way to get out of this is to go in the opposite direction, right? You have to push in and then hold it in order to get out. And then it's no problem ,right? It's really easy once you know the trick.

So the trick in the context of the coronavirus and other pandemics, is instead of opening up to normal, going in the direction you want to go in, you go in the other direction. Which means you lock down, you shut everything down, but you do it all the way. You do it the right way. And if you do it the right way it takes five to seven weeks in Switzerland. The smaller the zones you can carve out, the easier it is to do, the easier it is to get to zero in most of the country, the least economic impact it has. And then you can open up normally, and you open up progressively in zones. And again, it doesn't take a lot of time to get to the whole country.

And now we have tricks, right? We can do mass testing in areas where we still have a lot of cases. I mean, India has dealt with the biggest slum in, whatever, asia or the world. It's a million people in a square kilometer and a half area. And they know how to do it. Believe me, Switzerland can cope with the problem and get the cases down and get to zero. Okay?

So we can talk about all of the details, but why don't we go to questions? By the way, just to make one more statement. So, time is critical. And if anybody understands how to optimize time, it would be Switzerland. And the second thing is that essential travel is okay. We're not talking about hermetically sealing borders. I mean, it's a controlled variable. So what you want to do is get it down to as low as is possible, where possible includes allowing for essential travel. You can use permits, you can have buffer zones if there are areas that are still at risk, and so you can open them.

Yaneer Bar-Yam (31:46):

There's whole song and dance and details about how to do this right, and we can talk about it. But the basic idea is: go for elimination. It works. It's been done in many places. There's no reason it cannot be done in Switzerland. And then whether the neighbors come first, if Germany does it first or if you do it first, it doesn't really matter. Eventually it will be clear that this is the right thing to do and everyone will do it. All right?

That's my presentation. Thank you.

Danny Buerkli (32:14):

Thank you, Yaneer, for this. I'd like to start with one question which goes to the specificity of Switzerland, and this rare, you know quite well, which is the cantonal system. Which in many ways is very similar to the US system except everything compressed into a tiny space and much, much smaller with roughly 8 million inhabitants.

And naively, one would have thought that a really distributed decision-making system would be ideal for this kind of problem. And yet what we've seen is the opposite, which is power gets devolved to the cantonal level, or that's where it sits constitutionally to begin with, and then instead of effective action and some sort of a green zone model as you're describing it, what we're seeing is some kind of race to the bottom where everyone tries to keep as many things open as much as possible.

Yaneer Bar-Yam (33:08):

Right. Which doesn't work. Yeah. But the answer to that is there are some things that are better to be handled at that national level. But the main thing is actually just information. If localities knew that by going to zero they would have normal existence, they would do it. There was a town Vo, I guess, in Italy, that decided to get out of the outbreak in the beginning. It was one of the first places that were infected in Italy. And they just stopped the outbreak and they didn't have the disease, right? So there is this choice. And obviously, if people have examples. Some place did it, and was partying like New Zealand are now, right, and so on, then other people would be likely to copy.

So the main problem is a communication one. So the way to think about it is that the action actually happens in the community. Right? Remember that that's what we talked about in Ebola and so on. And we know that, with this outbreak, almost everything that has to be done is the responsibility of citizens, people who live in the community. And the role of government is actually mostly communication.

I mean, India is a huge country, right? With a billion people, over a billion people. And one of the things that has enabled them to be successful is apparently they have very good communication. Again, I'm talking with people there who are involved in the response and studying the response, and there's been apparently quite good communication and quite good public adherence.

So the problem is not sort of the regulation and the action itself, but the clarity of communication about what the goal is. And setting up at the national level and saying, "Look. We can get to zero. Let's do this. This is what it's about." There are these few steps that need to be done: protecting people from transmission, doing safe essential services, identifying cases early and isolating and quarantining them. I mean, we've been talking about this for months, right?

If we do all those things right, we can get to zero in a few weeks, let's do it. And by the way, the places that get to zero can open up normally and safely. We'll restrict travel between them so that others can get to normal. There's going to be a race in the other direction. There's going to be a race to zero because everyone is going to want to get there first.

Alenka Bonnard (35:43):

Now, Switzerland is not an island. I think we admire countries. We look at New Zealand and think, "Wow. This is fantastic." But we know that we aren't an island, we are around 8 million people and we have 300,000 people who are commuting every day. A lot of them are actually staff working in our hospitals, or in elderly homes. What do we do about this? We can't just...

Yaneer Bar-Yam (36:09):

Yeah. So I mean, this is not a new problem, right? I mean, this is... We talk about it as islands, but Australia is an island? I mean, look at them compared to all of Europe. I mean, there are eight states. And they had travel restrictions within a city, right? Within Melbourne, in order to prevent cases from transmitting from the core of the city out into the suburbs. And New Zealand had travel restrictions within Auckland, right? Between neighborhoods. I mean, everyone somehow has this idea also that they're so far away. But their tourism is like the UK. Right? I mean, I haven't looked at the tourism of Switzerland compared to it, but they have a lot of tourism there.

And in terms of essential workers again, you deal with this in the normal way. You set up a permit system, you tell them what the precautions are. It works. It's worked in multiple places. It's really not an issue. Luxembourg did it well. Right? Early in the first outbreak, they had travel restrictions that all of the workers could come in, the workers who had to work, and they gave them permits from three different countries. And Switzerland could do the same. Also within Switzerland you could do the same.

Again, this is not rocket science. It's also not a... The point is that this is not a fine machinery. Don't think about this like a watch where you have to get everything exactly right. This is a real world social system kind of thing. It's a public health intervention. It's messy. You don't have to have a hundred percent compliance. You don't have to have all the borders exactly shut. The door doesn't have to close exactly right, and whatever. It doesn't have to be exact.

What you have to do is realize that you have to switch regime. There is a regime of living with it that fails, and there's a regime of elimination which succeeds. And all you have to do is be in the right regime. And there's a lot of flexibility. If you do this thing well, if you do that thing well, or if you do something else a little bit less well, it doesn't matter. It's just going in the right directions. Remember, Vietnam did it. I mean, and so on. And all you really have to do is have exponential decline with a little bit of travel restrictions, and you can get there.

Danny Buerkli (38:38):

But, and just because this point, it's also been made in the chat already, what you're advocating for is tough. As you are saying, it needs to go the other way. And people are worried about compliance. People about worried about compliance already now. People are worried about compliance in the context of a vaccine, or vaccines becoming available. And arguably, the only thing that would be worse than this neither here nor there situation that we're in would be a situation where we lose people, and more stringent measures are not being accepted any more as legitimate.

Yaneer Bar-Yam (39:21):

So first of all, doing this, and even not succeeding, is much better than not doing this. People are so afraid of failure. It's just amazing. Right? You have to try in order to be successful. And you want me to give you a signed guarantee that you'll be successful. I don't mind signing it, of course. But if you want me to prove to you mathematically that it will work, actually I can do that too. The point is that it's actually not that hard. You have to first of all try. But it's very clear that you can succeed and you can succeed under so many different circumstances. And to claim that Switzerland couldn't be successful when countries that have so much less and so much less compliance and so much less... I mean, it just doesn't make any sense.

But not only that, the structure of the process itself helps you. Because you have local communities that their success reflects on them. In other words, if there happens to be a local community that takes it seriously and gets to zero, they get to open up normally. And so having that as a very obvious, and again, the communication is key. If you communicate about it clearly, the opportunity is tremendous for people to benefit from their own actions.

So if you want to tell me that it won't be successful anywhere in Switzerland, that would be kind of insane, right? But if it's successful some places in Switzerland, then that will create a huge impetus for others to be successful too. But I actually don't see why it would be a problem almost everywhere in Switzerland. I mean, again, there are a lot of places...

By the way, you know that this has been done in Atlantic Canada, in part of Canada. There are four provinces of Canada that are easternmost provinces, and they've done this successfully. So I mean, everyone keeps pointing to, "Hey, it's an island," or whatever. But hey, it just doesn't make any sense. Travel restrictions work. Essential workers can be allowed to go past, they are responsible. What you don't want is people coming in that are going to go partying because they're tourists and they don't care about the local community.

So it's really important that people have a sense of responsibility and are going to follow the precautions. But people who are workers, I mean, maybe there's 1 or 2% or something like that. I mean, I don't know what the numbers are. But you don't have to get everyone to do stuff in order to get to zero.

Danny Buerkli (42:11):

Thank you, Yaneer, for this rousing and rather convincing argument. We'd now like to open it up for questions from the floor.